–Written with Emily Powell, MACC

–Written with Emily Powell, MACC

Most families with a child experiencing symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) would like to know the reasons why their child has pediatric OCD (pediatric referring to children and adolescents under 18-years-old) and what caused it. They are hoping that perhaps identifying the root cause will somehow help with treatment options and decisions. Yet, it’s not that simple to pinpoint the exact “cause” or causes of OCD, nor is it likely to identify one single factor for a disorder as complex and varied as OCD. While it’s only natural for parents (and the child) to want to identify the exact cause in order to better guide treatment options, it’s important to note that OCD can be treated without knowing the exact cause.

Let’s look at some of the possible contributing factors of OCD, taking inventory of the neurobiological, cognitive and behavioral components that could develop the onset of OCD.

Specific genes

A risk factor that may contribute to the development of OCD in children is their specific genes and temperament. Children who are anxiety prone may have been born with a genetic predisposition towards anxiety. Furthermore, children are more likely to have an anxiety disorder if their parents have anxiety disorders. In some cases, rather than inheriting a specific anxiety disorder like OCD, a child might inherit a general tendency or predisposition to being emotional, fearful, high-strung, sensitive and highly reactive.

Temperament

In addition to specific genes, temperament may also play an important role in the development of anxiety disorders. A study by a Harvard psychologist discovered that about 10% of children have an anxious or fearful temperament from very early on in life. He referred to this temperament as “behavioral inhibition,” and found that children with this temperament are easily startled, scared, withdrawn, cry often and cling to adults. Children who experience this temperament have been found to have an over-reactive sympathetic nervous system, and also may experience the physiological arousal of anxiety more rapidly and intensely than children who are not behaviorally “inhibited.” However, it is the children who remain inhibited throughout childhood that appear to be at increased risk for an anxiety disorder compared to those who outgrow the inhibition.

Brain Function and chemistry

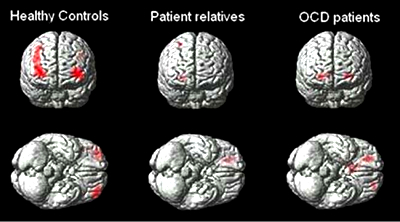

Brain function and chemistry are also thought to play a role in the development of anxiety disorders like OCD. For example, the basal ganglia of the brain and the neurotransmitter serotonin have been linked to OCD. Despite the high prevalence of OCD with children and adolescents, most of the research into the neurobiology of the affected brain networks and brain functions of the disorder comes from mainly from studies with adults. The onset of pediatric OCD often coincides with a developmental period in which cortical and

An excessive activation of cortical brain areas dealing with processing and a decreased activation of cortical brain networks using control, result in reduced cognitive control and a decreased ability to hold back inappropriate, repetitive cognitions and behaviors.

Stress

Stress is another contributing factor that could combine with life experiences, genetics and biological traits to impact the outcome of pediatric OCD. Yet, it’s critical to remember that stress does not cause anxiety or anxiety disorders, such as pediatric OCD. Significant life circumstances in a child or adolescent’s life, such as moving, starting school, or a conflict within the family can be stressful and increase anxiety in general. In fact, school may pose one of the most substantial anxiety-producing factors for children and adolescents. There is immense pressure to excel in school, perform well, and complete the ever-increasing homework assignment and school project lists. Children with a predisposition towards anxiety may take school requirements and responsibilities more seriously and may become more anxious when they cannot meet or achieve them according to their expectations.

Proneness to disgust

Recent research has uncovered that self-report measures of disgust proneness noticeably predict some OCD symptoms. Additionally, it has been observed that the neurocircuits involved in disgust processing may be related to OCD. This latest research is in line with the idea that OCD may reflect a false contamination alarm that is regulated by disgust, not only at a basic brain level, but also in terms of the psychosocial aspects of the disorder. Rather than intensely experiencing disgust or feeling disgust frequently, some people may feel cues of disgust and the experience of disgust as threatening, and such disgust sensitivity may bring about risk for some forms of OCD. Plainly, there is just an overestimation of the negative consequences of experiencing disgust.

It’s important to recognize that neither genes, temperament, brain chemistry, stress levels, nor proneness to disgust, are in and of themselves sufficient factors for a child to develop an anxiety disorder like pediatric OCD. The good news is that pediatric OCD can be treated and with great success. If your child is struggling with pediatric OCD, spend your focus and energy on their evaluation and treatment as soon as you can, and don’t dwell on the factors that may have contributed to the onset of their OCD.

David Russ

David Russ